Tags

Analytics, Big Data, books, Data Mart, Data Warehouse, Data Warehousing, enterprise data warehousing, Good Strat, Good Strategy, google, Martyn Jones, Martyn Richard Jones, News, sports, technology

Martyn Rhisiart Jones

29th January 2026

Hold this thought: To paraphrase the great Bob Hoffman, just when you think that if the Big Data babblers were to generate one more ounce of bull**** the entire f****** solar system would explode, what do they do? Exceed expectations.

I am a mild mannered person. However, one thing that irks me is hearing variations on certain themes. These themes include phrases like “Data Warehousing is Big Data.” Another is “Big data is in many ways an evolution of data warehousing.” Lastly, some say “with Big Data you no longer need a Data Warehouse.”

Big Data is not Data Warehousing. It is not the evolution of Data Warehousing. It is also not a sensible and coherent alternative to Data Warehousing. No matter what certain vendors will put in their marketing brochures or stick up their noses.

Many high-visibility screw-ups have carried the name of Data Warehousing, even when they were not Data Warehouse projects at all. Despite this, the definitions and strategies of data warehousing are well known. Its benefits and success stories are also recognized. They are in the public domain. They are tangible.

Data Warehousing is a practical, rational and coherent way of providing information needed for strategic and tactical option-formulation and decision-making.

Data Warehousing is a strategy driven, business oriented and technology based business process.

We stock Data Warehouses with data that, in one way or another, comes from internal sources. Optionally, it can also come from external sources. The data may be structured. Unstructured data can also be included optionally. The process involves extracting data from a source to target the Data Warehouse. This includes scrubbing that data, transforming it, and loading it. This process is known as ETL.

Data Warehousing’s defining characteristics are:

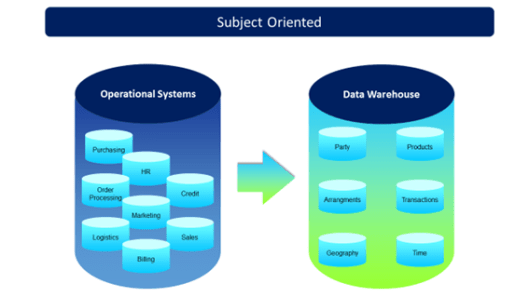

Subject Oriented: Operational databases, such as order processing, payroll, and ERP databases, are organized around business processes. They focus on functional areas. These databases grew out of the applications they served. Thus, the data was relative to the order processing application or the payroll application. Data on a particular subject, such as products or employees, was kept separately. This often led to inconsistencies across a number of different databases. In contrast, a data warehouse is organized around subjects. This subject orientation presents the data in a much easier-to-understand format for end users and non-IT business analysts.

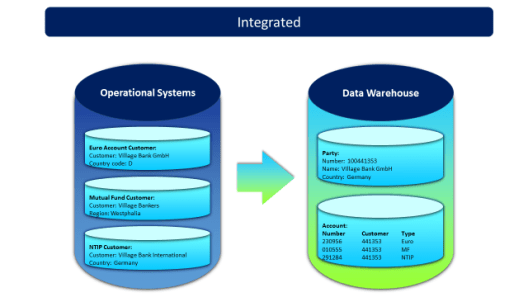

Integrated: Integration of data within a warehouse is accomplished by making the data consistent in format, naming and other aspects. Operational databases, for historic reasons, often have major inconsistencies in data representation. For example, a set of operational databases may represent “male” and “female” by using codes such as “m” and “f”. They might use “1” and “2”, or “b” and “g”. Often, the inconsistencies are more complex and subtle. In a Data Warehouse, on the other hand, data is always maintained in a consistent fashion.

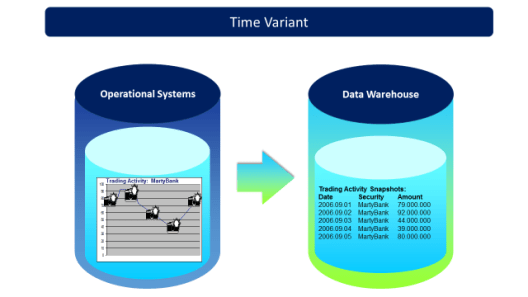

Time Variant: Data warehouses are time variant in the sense that they maintain both historical and (nearly) current data. Operational databases, in contrast, contain only the most current, up-to-date data values. Furthermore, they generally maintain this information for no more than a year (and often much less). In contrast, data warehouses contain data that is generally loaded from the operational databases daily, weekly, or monthly. This data is then typically maintained for a period of 3 to 10 years. This is a major difference between the two types of environments.

Historical information is of high importance to decision makers, who often want to understand trends and relationships between data. For example, a Liquefied Natural Gas soda drink product manager might want to analyse promotional impacts. They might study how coupon promotions affect sales. This information is almost impossible to determine with an operational database. In most cases, it is certainly not cost effective.

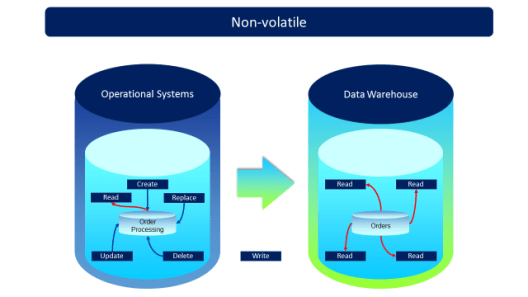

Non-Volatile: Non-volatility means that after the data warehouse is loaded, there are no changes performed. Inserts or deletes are not performed against the informational database. The Data Warehouse is, of course, first loaded with cleaned, integrated and transformed data that originated in the operational databases.

We build Data Warehouses iteratively. We add a piece or two at a time. Each iteration is primarily a result of business requirements. Technological considerations do not primarily drive iterations.

Each iteration of a Data Warehouse is well bound and understood. It is small enough to be deliverable in a short iteration. It is also large enough to be significant.

Conversely, Big Data is characterised as being about:

Massive volumes: so great are they that mainstream relational products and technologies such as Oracle, DB2 and Teradata just can’t hack it, and

High variety: not only structured data, but also the whole range of digital data, and

High velocity: the speed at which data is generated, transmitted and received.

These are known as the three Vs of Big Data. They are subject to significant and debilitating contradictions. This occurs even amongst the gurus of Big Data (as I have commented elsewhere: Contradictions of Big Data).

From time to time, Big Data pundits criticize Data Warehousing. They say it cannot cope with the Big Data type hacking they are used to carrying out. This is a mistake made by those who fail to recognize a false Data Warehouse when they see one.

So let’s call these false flag Data Warehouse projects something else, such as Data Doghouses.

“Data Doghouse, meet Pig Data.”

Failed or failing Data Doghouses fail for the same reasons that Big Data projects will frequently fail. Both will almost invariably fail to deliver artefacts on time. They will not meet expectations. There will be failures to deliver value. It will be difficult to return a break even in costs versus benefits. Of course, there will be failures to deliver any recognisable insight.

Failure happens in Data Doghousing (and quite possibly in Big Data as well) for several reasons. There is a lack of coherent and cohesive arguments for embarking on such endeavours in the first place. Additionally, there is a lack of real business drivers. Lastly, there is a lack of sense and sensibility.

There is a willing tendency to ignore advice. People often disregard those who warn against joining in the Big Data hubris. Why do so many ignore the ulterior motives of interested parties? These parties are solely engaged in riding on the faddish Big Data bandwagon. They aim to maximise the revenue they can milk off punters. Why do we entertain pundits and charlatans who praise Big Data? Meanwhile, they cultivate an ignorance of data architecture, data management, and business realities.

Some people say that the main difference between Big Data and Data Warehousing is this: Big Data is technology. Data Warehousing, on the other hand, is architecture.

Now, whilst I totally respect the views of the father of Data Warehousing, I also think he was too kind. He was too kind to the Big Data technology camp. I respect his views, yet I feel he was too accommodating toward the Big Data technology camp. However, of course, that is Bill’s choice.

If Oracle gave me the code for Oracle 3, I could make significant improvements. I would add 256 bit support and parallel processing. I would also give it an interface makeover. It would then be 1000 times better than any Big Data technology currently in the market. Keep in mind, that version of Oracle is from about 1983.

Therefore, Data Warehousing has no serious competing paragon. Data Warehousing is a real architecture. It has real process methodologies. It is tried and proven. It has success stories that are no secrets. These stories include details of data, applications, and the names of the companies and people involved. We can point at tangible benefits realised. It’s clear, it’s simple and it’s transparent.

Just like Big Data, right?

Well, no.

See what I mean?

The next time someone tells you that Big Data will replace Data Warehousing, correct them. You might hear that Data Warehousing is Big Data. If you encounter any variations on that sort of ‘stupidity’ theme, confidently tell them to take a hike. Rest assured, you are on the side of reason.

Many thanks for reading.

More perspectives on Big Data

Aligning Big Data: http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/aligning-big-data-martyn-jones

Big Data and the Analytics Data Store: http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/big-data-analytics-store-martyn-jones

A Modern Manager’s Guide to Big Data:http://www.linkedin.com/pulse/managers-guide-big-data-context-martyn-jones

Core Statistics coexisting with Data Warehousing

Accomodating Big Data

And a big thank you to Bill Inmon (the father of Data Warehousing and of DW 2.0)

Retrospect 2026

The above retrospective piece is by Martyn Rhisiart Jones. It is dated 29 January 2026 but originates from much earlier. It serves as a well-aimed corrective. It arrives in an era when data architectures are still being sold as fashion items. They should be enduring infrastructure. Jones, with calm exasperation from witnessing too many vendor slide decks promising revolutions, restates a case. Those revolutions never quite materialise. It feels almost quaint in its clarity. Data warehousing is not Big Data. It is not its evolution or its replacement.

Jones channels the spirit of Bill Inmon, the acknowledged father of data warehousing. His foundational definition remains subject-oriented, integrated, time-variant, and non-volatile. This definition is a model of precision. He contrasts this with the famous “three Vs” of Big Data (volume, variety, velocity). He dismisses these as riddled with contradictions. They are often deployed as marketing vapour. The frustration is palpable. Just as one thinks the hype has peaked, it surges again. This risks what Bob Hoffman might call an explosion of the solar system under accumulated nonsense.

What irks Jones most is the persistent conflation. Phrases like “Big Data is an evolution of data warehousing” are common. Others say, “you no longer need a data warehouse.” They appear in brochures and conference keynotes. This often originates from parties with a vested interest in selling new platforms. He labels failed warehouse projects “Data Doghouses.” These are ill-conceived efforts lacking business drivers, coherent architecture, or sensible scoping. He suggests Big Data initiatives suffer similar fates for similar reasons. These include overpromising, under-delivering value, and ignoring the hard work of proper data management.

The strength of Jones’s argument lies in its insistence on first principles. Data warehousing, he reminds us, involves architecture first. Technology comes second. It is a business-oriented process built iteratively around real requirements. It delivers consistent, historical, integrated views for decision-making. It succeeds where it is bounded, focused and driven by tangible needs. These are qualities that the more amorphous Big Data paradigm often lacks.

In 2026, the dust is settling on a decade of lakehouses, cloud migrations, and AI-infused analytics platforms. Jones’s retrospective feels timely. The market has not abandoned data warehousing; it has evolved it. Cloud-native warehouses handle larger scales, real-time ingestion and even unstructured elements more gracefully than their on-premise forebears. Yet the core discipline, integration, consistency, historical depth, endures, often quietly powering the flashier tools layered on top. Jones is no Luddite railing against progress. He acknowledges technological advances. He even cheekily suggests he could modernise Oracle 3 from 1983 to outpace much of today’s Big Data stack. He advises caution and warns against overconfidence. Chasing fads without architecture leads to repeated failures, missed deadlines, and elusive ROI. It also results in absent insight.

The lesson, as Jones delivers it with polite fury, is straightforward. When someone claims Big Data has supplanted data warehousing, the response should be firm. It should also be evidence-based. Some people suggest the two are interchangeable. The response should be firm. It should also be evidence-based. The warehouse was never broken in concept; too many implementations were broken in execution. Reason, not revolution, wins in the end.

In an industry prone to overstatement, Jones offers a rare commodity: sobriety. And in data as in life, that tends to age rather well.

Discover more from GOOD STRATEGY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.